Last updated: June 25, 2024

5 mins read

Are you finding it difficult to achieve restful sleep or feeling drained despite using your sleep tracker? Discover how combining sleep data from devices like Oura rings or Apple Watches with blood biomarker data can transform your health and well-being.

Many of us rely on wearable devices to monitor our sleep, hoping to uncover the secrets to better rest and more energy. However, these devices often leave us with more questions than answers. It’s not just about tracking steps or sleep stages; it’s about understanding the deeper connections between different aspects of our health. If you’re looking to improve your diet, exercise, or sleep habits, the following insights can help you determine what changes might enhance your overall well-being.[1]

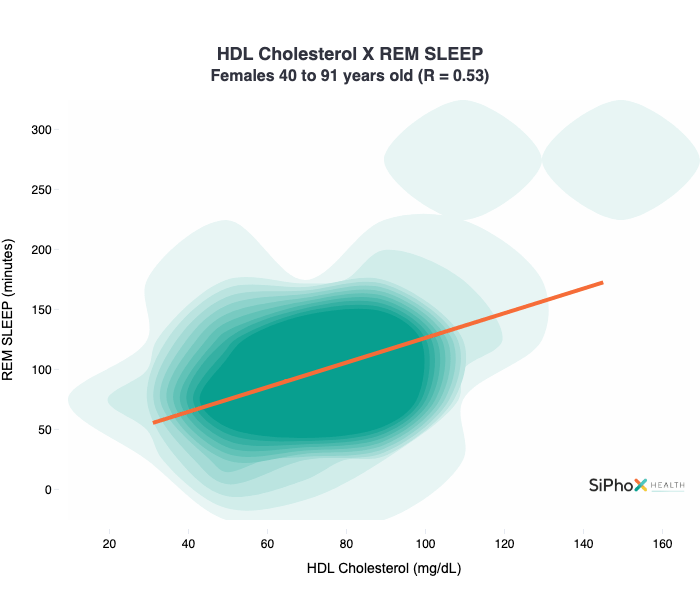

To explore these connections, we analyzed SiPhox user data to identify relationships between blood biomarker data and connected wearable device data. Surprisingly, we discovered a strong correlation between lipids and sleep data, particularly in women over the age of 40. These findings could provide valuable insights for those looking to make informed changes to their health routines. [2]

First, a quick explanation of our data exploration methodology and a few definitions

Methodology

Wearable data was averaged over the two weeks preceding the associated blood tests.

For correlation analysis, we used Pearson’s correlation coefficient (a measure of the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two variables) to measure the strength and direction of the linear relationship between the two datasets. We further visualized these relationships by creating plots with an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression line (a straight line that best fits the data points), which helped illustrate the trend and strength of the correlations. This methodology allowed us to effectively identify and visualize meaningful correlations within the data. [3] [4]

Cholesterol — the Good, the Bad, and the Transport:

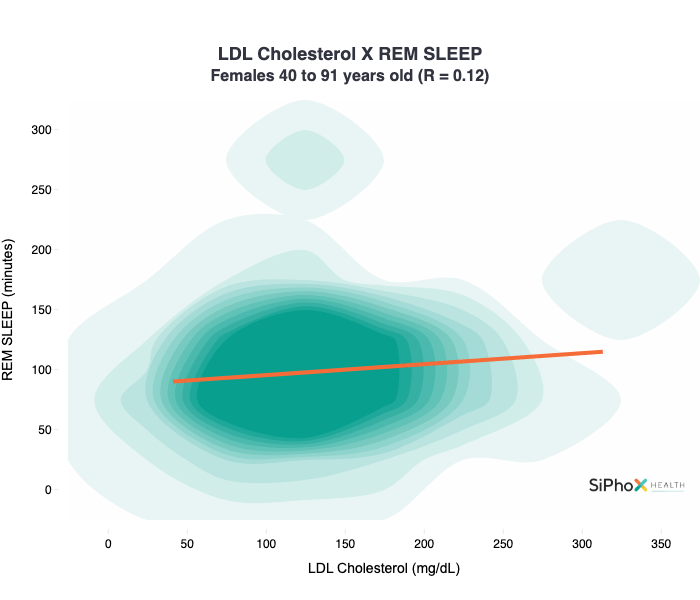

Cholesterol can be categorized into HDL-C (high-density lipoprotein cholesterol) and LDL-C (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol), commonly referred to as “good” and “bad” cholesterol.

LDL-C (“bad”) cholesterol is deposited into the arteries, which increases the risk of cardiovascular disease. [5]

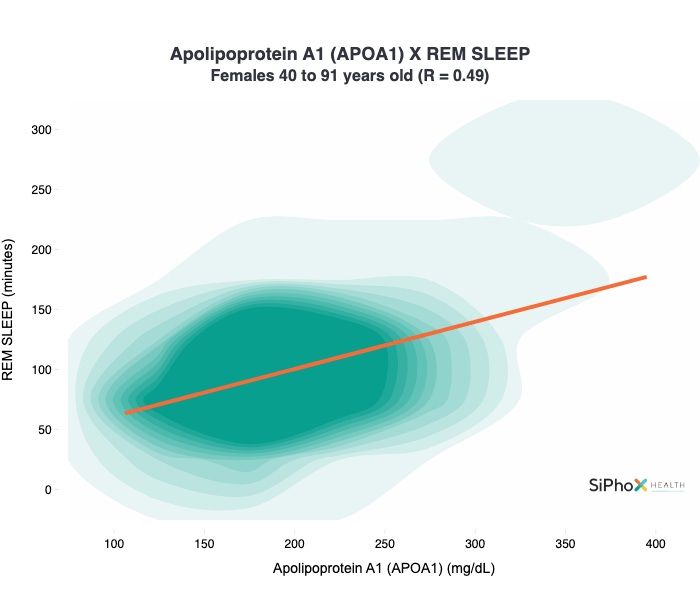

HDL-C refers to the cholesterol carried by Apolipoprotein A1 (APOA1) (a type of protein that carries cholesterol in the blood) -containing HDL particles. HDL particles pick up harmful cholesterol in the arteries and then carry everything to the liver (directly or indirectly), where cholesterol is repurposed or removed. [6] [7]

Rapid Eye Movement Sleep:

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is a phase that lasts approx. 25% of your total sleep duration, where (alongside other activities) your brain rests and repairs itself so you can wake up feeling refreshed and energized. [8]

The cholesterol-sleep relationship in women over the age of 40

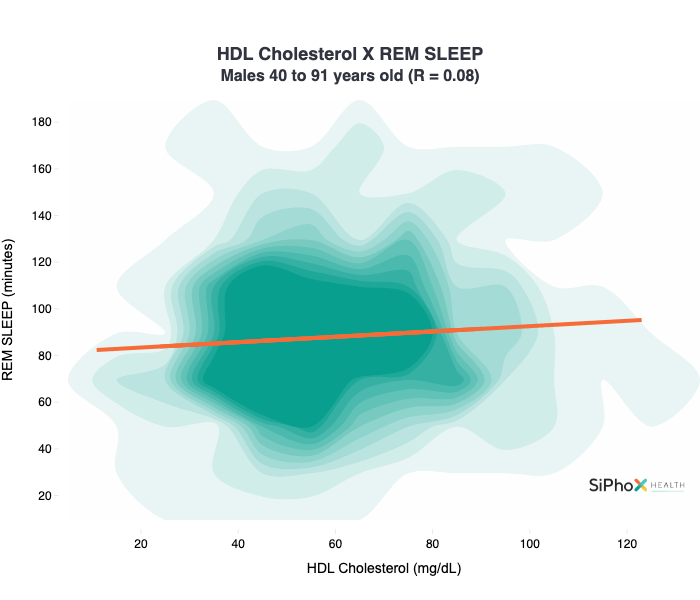

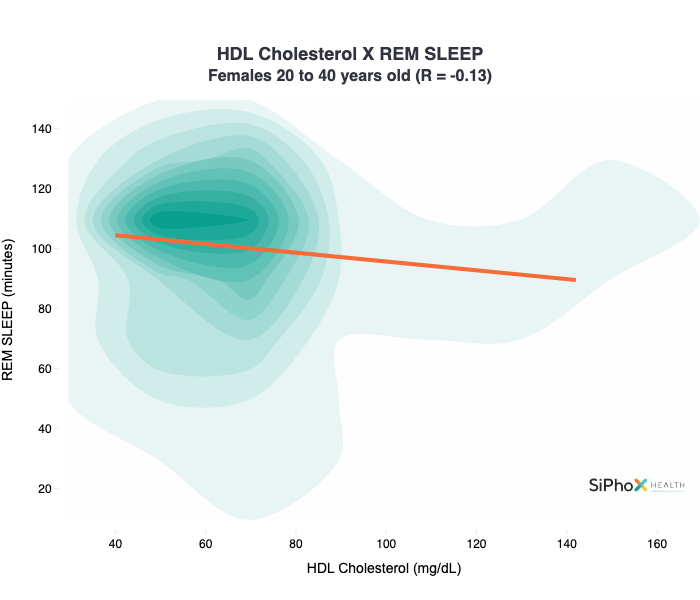

There was a strong positive correlation between HDL-C and REM sleep for women over 40 years of age. Interestingly, there was no significant correlation between the same markers in neither men of the same age group (correlation coefficient = 0.08) nor in younger women (correlation coefficient = -0.13).

Unsurprisingly, we saw a similarly positive correlation between APOA1 and REM sleep, which is to be expected given the relationship between HDL-C (passenger) and APOA1 (vehicle).

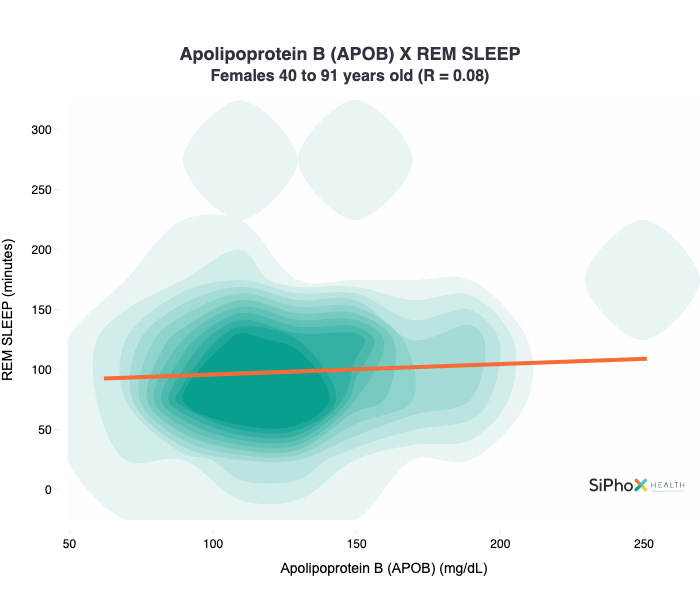

For additional graphs on the relationship between bad cholesterol (LDL-C, APOB) and sleep data in the same age group, please refer to the Supplementary Data section.

How does this differ for men?

Given the strong correlation in women, one might assume that there’d be a similar correlation in men. But our data says otherwise.

The correlation between HDL-C and REM, for men over 40, was only 0.08, which is essentially a non-existent correlation and certainly a far weaker one than the 0.53 correlation coefficient in women of the same age group! For all intents and purposes, our data indicates that there is no correlation between cholesterol biomarkers and sleep data in men over 40.

It is unclear whether the relationship we’re observing is causative or correlative. Perhaps one of the two, HDL-C or REM sleep, impacts the other. Just as likely, they’re both independently impacted by another set of biomarkers or activities, such as an active lifestyle or hormone status.

That being said, here are a few mechanistic connections between REM and HDL-C:

- HDL-C particles have significant anti-inflammatory properties. Chronic inflammation is known to disrupt sleep patterns. So this reduced inflammation could contribute to more stable and prolonged REM sleep.

- HDL-C particles support endothelial function, which is vital for healthy blood circulation. Improved endothelial function could improve circulation to the brain during sleep, and subsequent REM sleep duration. [9]

These connections exist in both men and women, though. If either or both of these are the root cause of the correlation, then why don’t we see this in men? Or a younger cohort of women?

If you’re interested in seeing how your cholesterol and sleep are correlated, pick up an at-home blood testing kit from SiPhox. You’ll receive results and insights in your SiPhox dashboard within a few days of collecting your sample.

Supplementary Data

Correlation between HDL-C and REM sleep among males aged 40 and older.

Correlation between LDL-C and REM sleep among females aged 40 and older.

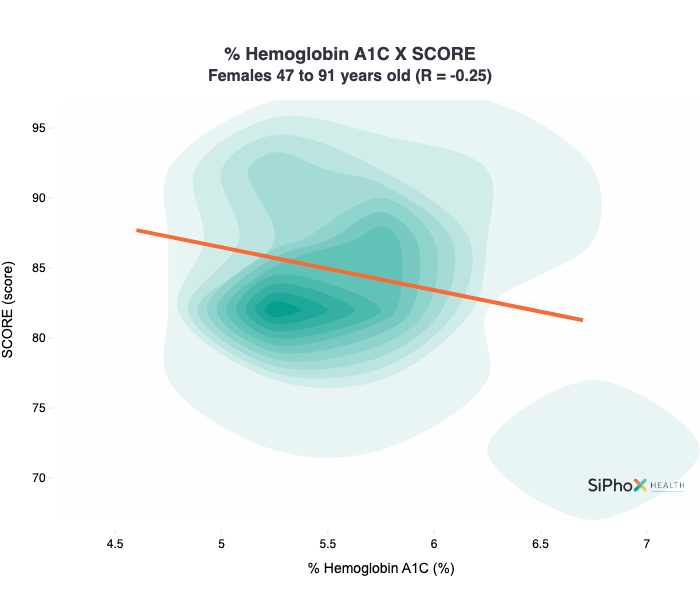

Correlation between hbA1C and Oura sleep score among females aged 47 and older.

Correlation between HDL-C and REM sleep among females aged 20 to 40 years.

Correlation between APOB and REM sleep among females aged 40 and older.

References